In 2023, drug overdose deaths fell for the first time since 2018.

While drug deaths remain unacceptably high — at more than 100,000 last year — at least we’re finally moving in the right direction.

But there is a part of the population where deaths have increased significantly: adolescents, teenagers and young adults.

Research shows that an average of 22 Americans aged 14 to 18 will die of drug overdose each week through 2022.

These researchers identified hot spots — such as Maricopa County, Ariz., and Los Angeles, Calif. – – where youth overdoses are the highest.

Here, fake pills containing fentanyl have flooded the market. Pills are cheaper than ever and easily accessible on social media platforms loved by young people.

Our government has been trying to prevent young people from using drugs for over a century. These campaigns have mostly involved scare tactics focused only on the consequences of drug use.

But while they may make for good advertising, such strategies usually fail as children tune them out.

But in the age of fentanyl, we must trade fear-mongering for accurate and compassionate drug education based on science. Sadly, many states are failing to catch up.

Recently, I spoke with grieving parents and families who are fighting for strong and effective drug education and prevention. As someone in long-term recovery, I can sympathize. My drug education was a failure.

Kids like me who grew up in the 1980s remember DARE officers coming into our classrooms warning us about the dangers of drugs. It was the wrong message and the wrong messenger.

What we needed instead were practical tools and information that we could understand and identify with.

Fortunately, there are proven strategies to reduce the misuse of harmful substances. Take the hugely successful (non-governmental) youth-focused anti-smoking initiative The Truth. The truth worked because the campaign understood how teenagers think.

The goal was to create a series of messages that never sounded preachy, that never condemned or blamed smokers; who told teenagers that Big Tobacco lied to them and then led teenagers to rebel against him.

Young people who saw the Truth ads reported that they were 66% more likely to say they would not smoke in the next year.

We need a national Truth About Fentanyl campaign. And it must begin by understanding the nature of the problem we are now dealing with.

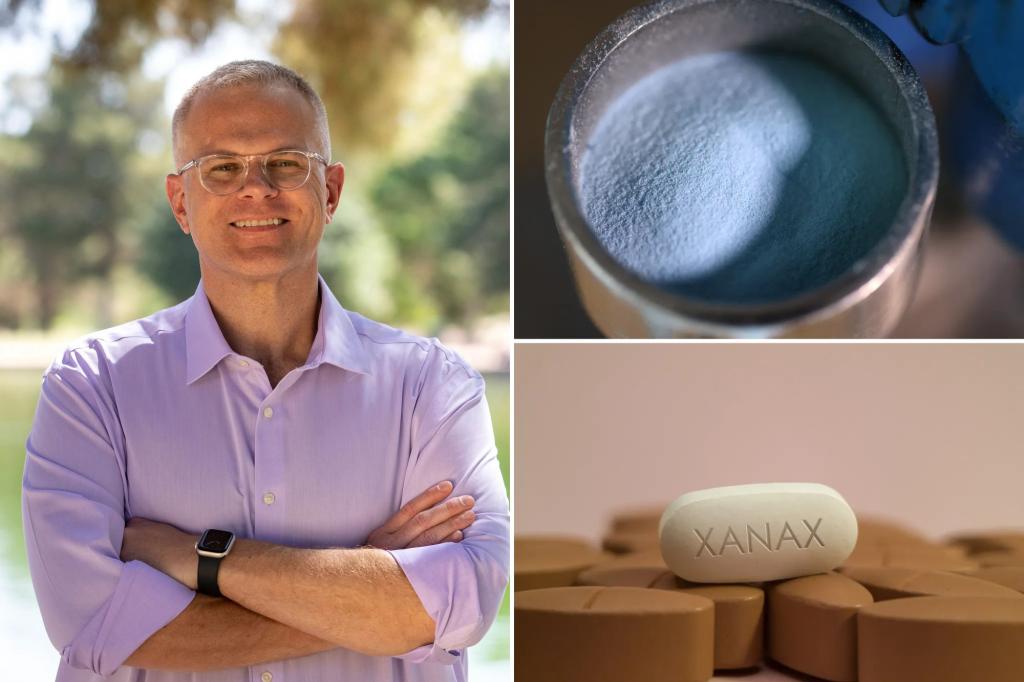

Most young people who die from fentanyl do so after taking counterfeit pills.

Fake but deadly, these pills are crushed and molded into popular drugs like oxycodone, Xanax and Adderall.

Most have no physiological tolerance to powerful synthetic opioids, so taking just one fake pill can be deadly.

This is the new reality of pill-taking in America, and it means we have to adapt to it.

The Drug Enforcement Administration wasn’t kidding when it launched the nationwide “A Pill Can Kill” campaign. The DEA slogan is concise and memorable.

But I am concerned that young people are still not hearing the government’s message, even if “A pill can kill” is technically true.

Just as Truth ads realized they were competing with Big Tobacco, the DEA’s message is competing with a culture that tells us all every day that there’s a pill to fix everything—that pills are a quick and easy fix for what troubles us. And that’s a hard reality to undo.

To reach children with a message that really resonates, we must also think locally. For example, the Wolfe Street Foundation program in Arkansas was the state’s first community-based youth recovery program designed for students in grades 7-12.

The program establishes a peer model, meaning that young people who have been affected by substance use are also messengers of the program. Wolfe Street recognizes that peers are essential to getting young people to actually heed fentanyl’s warnings.

Parents still have an important role to play, too. I recommend that parents visit the Advertising Council, which offers advice for adults on how to talk to their children about fentanyl.

Experts like Dr. Scott Hadland, a pediatrician in charge of adolescent and youth medicine at Mass General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, says it’s essential to be honest, compassionate and open when talking with children about complicated and difficult topics like drugs.

Stanford Medical School recommends that drug education for young people focus on three main pillars: First, the curriculum must be scientifically based.

Second, it should be engaging and interactive because that’s how young people learn best. Finally, it must be compassionate. Drug education must take into account the fact that most young people will not try substances at all. And this is good news.

But those who try them at some point are probably struggling with other aspects of life, such as mental health, family stress, or some physical or emotional pain.

We live in a culture that celebrates quick fixes and pills for every ailment. That is why saving children from fentanyl will be an uphill battle that we must all fight together.

Ryan Hampton is a national addiction recovery advocate and author of the upcoming book “Fentanyl Nation: Toxic Politics and America’s Failed War on Drugs” to be published by St. Martin’s Press on 24 September.